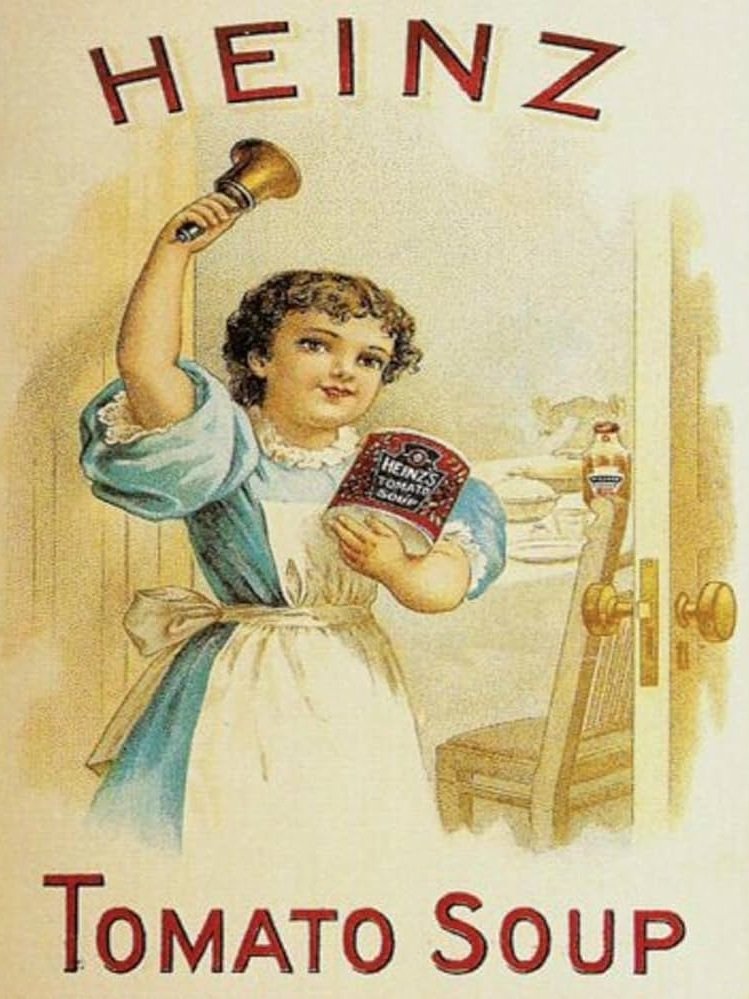

The Secret Life of Housewives & Heinz Tomato Soup

I am, much to the perplexity of my peers, a great purveyor of two much maligned phenomena: Heinz tomato soup, and housewives.

The two have a surprising amount of similarities. Both are popular with babies; whilst motherhood and cleaning can be seen as key to the tradition of housewifery, Heinz tomato soup has entered the culinary canon of our childhood as a suppertime staple and soother in sick days.

Both have been through highs and lows. Housewives have oscillated up and down the social ladder from downtrodden house-labourers, to a status that better approximates the title ‘Lady of Leisure’. Equally, Heinz tomato soup, which was first created by Howard Heinz during the 30s depression in America as an economical food option, has since been stocked in fancy pants Fortnum & Masons.

I don’t think there is anything to romanticise about the days when scrubbing porches whilst perpetually pregnant was order of the day for all females who weren’t filthy rich.

Before we go any further, I think it’s important to make some key distinctions. I tend to focus my veneration on the latter part of housewife history, preferring to think of the 20th century as the ‘heyday of housewives’. Anything before then is a grim testament to the difficulties of human life. I don’t think there is anything to romanticise about the days when scrubbing porches whilst perpetually pregnant was order of the day for all females who weren’t filthy rich.

Meanwhile the Grand Dames who escaped the actual labour of domesticity thanks to servants, wiled away their time in an equally permanent depression. Having succumbed to societal pressures and married a suitable man, it seems they spent much of their life bound, bemoaning fate and bored. Just think of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Ibsen’s misused ‘doll’, Nora Hemler in The Doll’s House, or even the many ladies liberally peppering Jane Austen novels whose only concern is the creeping horror of buying the wrong ribbons, marrying the wrong person, or worst of all, not marrying at all.

No; into that murky history of the housewife I do not care to trespass. Instead I sentimentalise a different era, a slippers and soap genteel sort of housewifery. A place where the load of daily labour was already eased by the invention of appliances. A cosy, middle class housewifery, full of women married to dentists, accountants, tax inspectors, chemistry teachers and other such reputable characters. A time when the majority of women weren’t living in lavish quarters but were not really expected to earn their own living either. This housewife I am transfixed by.

No longer is she chained to chores, she may roam freely and act devilishly.

After all, who are the most devious, most dastardly, of Roald Dahl’s adult story characters? Undoubtedly, the Housewives. Dahl’s married women connive. They leave their tiresome husbands trapped in elevators. They engage in steamy affairs. They have a pathological yearning to cheat in card games. They trick, and they steal, and they love fur coats. Occasionally they embalm young men. If you’re not acquainted yet with this most fascinating and scheming group of fictional characters, acquaint yourself you must. Now it seems to me that Dahl was able to create this plethora of stories because the role of the housewife had become decidedly vague. No longer is she chained to chores, she may roam freely and act devilishly. So what is the mark of the modern day housewife? What does she do?

We have a lot of ideas about housewives, that much is for sure. In popular media, ‘Bored Housewives’ bang the plumber in bad pornos. ‘Real Housewives’ go on TV where they’re filmed flinging glasses of fine Chardonnay over each other and fingering their husbands’ cheque books. ‘Classic Housewives’ groom dogs, burp babies and grumble their way around parenting blogs. There seems to be scant similarity amidst these differentiating stereotypes. The only thing I feel sure of is that we have these ideas of housewives because, once again, we know so little about what they really do, that we project on them. Away from the porn, reality TV and blogs, the mystery of the housewife is that we don’t know anything about her.

I would say that housewives nowadays are in poll position. The housewife is the only remaining member of our society who can hide without triggering suspicion. She has no co-workers, she has no competitors. Her family and friends are likely preoccupied at their jobs all day. So are her neighbours. Her children are probably completing some stage of their miserable education, whilst any public snooping devices like CCTV are shut out by the impenetrable walls of her house. Inside her house, the housewife is an unknown quantity. What it boils down to is this: a housewife is a woman that nobody is watching.

The housewife is the only remaining member of our society who can hide without triggering suspicion.

Let me bring it back to Heinz. Here you have to ask yourself, what do we really know about Heinz tomato soup? How did it come about? What are actually the contents in its can? Only one thing can we be wholeheartedly sure of; it has very little to do with tomatoes.

As innocent as the can of soup – that staple of your cupboard; holy grail of the lazy; ever-lurking shadow on the supermarket shelf – is the housewife. These two fixtures are everywhere, unassuming, unremarkable… and yet. A housewife is a woman with enough time to develop an imagination. Someone who can live outside the social bracket where all our thoughts and actions are influenced by the media. These days the office worker is the poor soul trapped in the vice grip of society, not the the humble housewife.

Whatever the reality, we cannot know it. Us – with our 28 days’ holiday; round of lager after work; PowerPoint presentation; firewalls on the office internet; Hammersmith tube delays – lives. For all we know, a housewife might be made out of tomato soup and tomato soup might be made out of housewives. Stranger things have happened.

But if nothing else, housewives and Heinz tomato soup are both excellent examples of a rich internal life we can know nothing of.