What’s in a Selfie?

Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia taking a selfie

On March 31st the Saatchi Gallery will launch a new exhibition named ‘From Selfie to Self-Expression’. The show will explore the history of the selfie from the old masters to the present day, juxtaposing works by Van Gogh, Tracey Emin and Cindy Sherman with some of today’s most retweeted celebrity snaps. It’s not the first time an art gallery has dedicated space to our obsessive self-documentation, but a few eyebrows have been raised. Why do art historians, journalists and bloggers consider it necessary to debate the worth and purpose of the humble selfie? The answer is trickier than might be expected, and – like a selfie of our society – tells us not just about who we are, but about who we want to be.

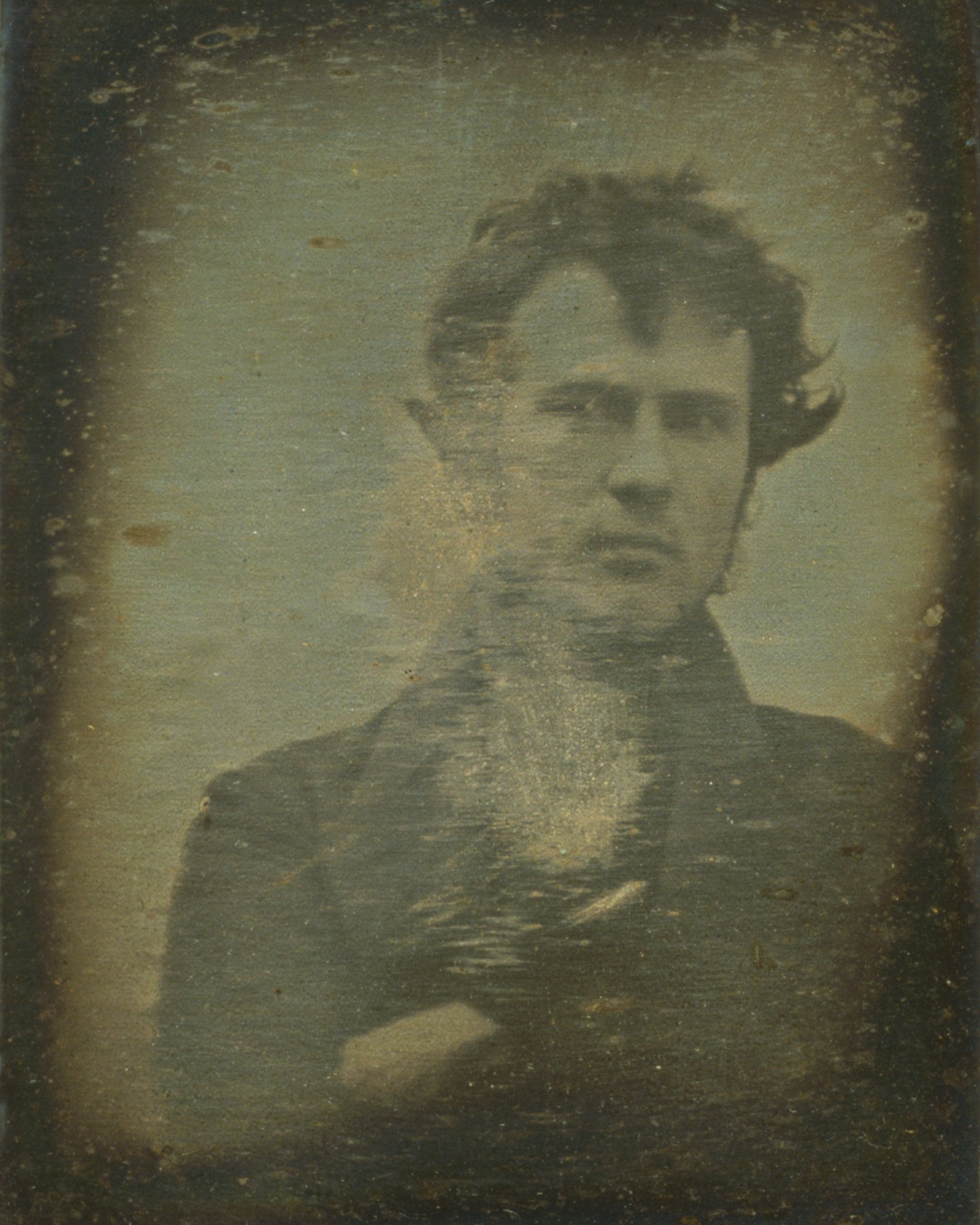

For as long as people have been taking photos, they’ve been taking photos of themselves. In fact, one of the first ever photographs of a person – a daguerreotype taken by Robert Cornelius in 1839 – was a selfie. As cameras slowly become more widely available, we reach Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia in the year 1914, who used a mirror to take her own picture at the age of 13. She wrote in a letter to a friend at the time, ‘I took this picture of myself looking at the mirror. It was very hard as my hands were trembling.’ Do bathroom-mirror teens today, taking their first furtive steps towards selfiehood, still tremble in the same way?

There are almost 300 million photos uploaded to Instagram tagged #selfie.

Then the tech speeds up – digital cameras enable limitless snaps, phones start sprouting front-facing cameras in 2003, and by 2014 we have the selfie-stick. Alongside these developments in hardware, a constellation of image-hosting sites and social networks sprang up to receive our every photographic emission. Quite suddenly, we were all marketing our happy, successful lives to our friends, and FOMO was born.

At the time of writing, there are almost 300 million photos uploaded to Instagram tagged #selfie. The word ‘selfie’ has been traced back as far as an Australian forum in 2002, and eleven years later it was the Oxford Dictionary’s word of the year, defined as ‘a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.’ Along the way, we’ve had a few landmarks – Akihiko Hoshide’s selfie from space went viral in 2013 (though Buzz Aldrin had actually taken the first, almost fifty years earlier), while a selfie taken in 2011 by a crested black macaque in the Indonesian jungle launched a curious copyright debate about whether the primate could own the rights to its own image. Five years later a US District Judge ruled that no, it couldn’t.

Selfiecity, a research project that analysed 120,000 selfies from five major cities around the world, created a portrait of the average selfie. The majority of selfies are taken by women, with a median age of 23.7 and an average head tilt of 12.3°. The subject’s expression varies by country – Bangkok and Sao Paulo are are all smiles, while Moscow and Berlin are more dour.

Is it all just an exercise in narcissism? It’s easy to picture this average selfie-taker, picking the best of 200 duckfaced snaps, uploading it to Instagram and anxiously waiting for the likes and comments to roll in. Stephen Marche memorably described the phenomenon as the ‘masturbation of self-image’. The app market supports this view, offering tools for us to easily remove wrinkles and blemishes, whiten our teeth and tan our skin, or even apply the ominous-sounding auto-slim filter.

But it’s not so simple. There’s a counter-current of selfie-takers using the medium to actively defy prevailing beauty standards, proudly showing off their stretch marks, skin conditions or unconventional shapes. The Instagram page #effyourbeautystandards, run by plus-size model Tess Holliday, has over 300,000 fans following its body-positive example. So, while selfies can certainly be seen as a trend that hammers punishingly narrow definitions of beauty into impressionable minds, they can also be seen as a tool of empowerment: a weapon for the insecure to claim their beauty, for the unrepresented to represent themselves in the media widescreen.

Whether we like it or not, we live in an age of personal branding. Here, celebrities are dredged up from the deepest Mordors of Youtube based solely on view count and successful people can lose their families and livelihoods overnight because of a single off-colour tweet. If we’re going to be judged on our online profile, who can blame us for curating it, for trying to control how others see us?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we seem less interested in other peoples’ selfies than in our own. A recent study from a German university showed that while 77% of their sample group took regular selfies, 82% of them would rather see any kind of photo on social media other than someone else’s selfie. We judge the selfies of others more harshly than the ones we upload – ‘theirs are vain, mine are ironic’. Perhaps what underlies the epidemic of selfie-hatred is a simple case of double standards.

The ease of taking a selfie democratises it as a medium of self expression.

Some locate the selfie in the artistic tradition of self-portraiture. The Saatchi gallery certainly does, by placing Kim Kardashian next to Rembrandt, the godfather of the self portrait. Rembrandt charted his aging process and a lifetime of stylistic shifts across more than 90 self portraits. The self portrait, like the selfie, is an examination of self-image. We’re showing people not how we look, but how we think we look, or how we want to look. A recent study from the University of Parma showed that selfies by non-professional photographers show a slight bias for the left cheek, a fact also observed in painted portraits across history. Perhaps the selfie generation, like artists of yore, are just introspecting with the artistic tools available to them. And for those who claim there’s an inherent narcissism in selfies absent from classical portraiture, think again – Henry VIII had his own auto-slim filter in the form of painter Hans Holbein, whose famous portrait doesn’t honestly depict the corpulence of a man who had to be winched up onto his own horse.

You could argue that a selfie doesn’t demand the artistic skill of a self portrait in watercolour. This introduces the question: does something have to be difficult to create to be labelled art? One thing, however, is clear – the ease of taking a selfie democratises it as a medium of self expression.

Some see the images not as art but as documents of our time, a photo-journal used to memorialise and broadcast experience. These could prove a fascinating historical artefact in the future – as a Vulture article pointed out, ‘imagine what we could see if we had millions of these from the streets of Imperial Rome.’

Others see the selfie as a particularly modern form of communication, like a personalised emoji. It may be easier to communicate your mood, location or daring new haircut to your friend with a quick photo than using words. Art historian Geoffrey Batchen wrote that selfies represent ‘the shift of the photograph [from] memorial function to a communication device.’

The upcoming Saatchi exhibition is a timely contribution to the debate about what a selfie is and what it’s for. Any given selfie could be self expression, a documented memory, pictorial communication, shameless self-marketing or a cry for attention. Most likely, it’s a mixture of the above. This polyvalent character makes the selfie a nightmare for those who seek to define art and culture. Yet the selfie has arisen as a response to our increasingly unbordered society, where online and offline worlds collide and truth, image and trust have never been easier to question.

Ultimately selfies are just a tool. Society is rapidly arriving at a point where every person has to make moral decisions about how they use the technology available to them. The selfie is still young. It’s up to us to decide what it’s going to be.